Unsolicited Press

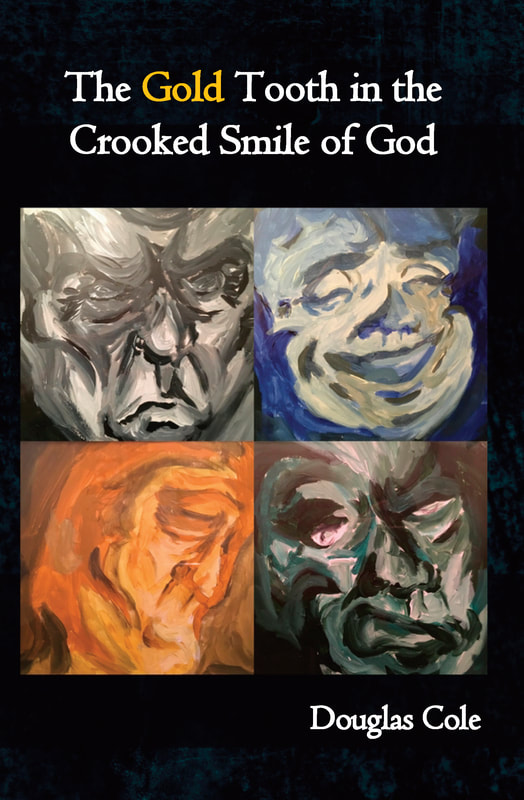

The poems in this generous collection mirror the chosen title. One after another they engage our not-so-secret foibles, desires, rants & ravages. & they leap around, which keeps us slightly off-balance but engaged & curious, what will the poet come up with next? Douglas Cole’s latest collection of poems titled The Gold Tooth in the Crooked Smile of God is a challenge from beginning to end, where the outcome varies, as it does in all good poetry, according to what the reader brings to it or fashions from it while reading. Cole is unusually adept at leaving enough unsaid to require the reader to enter what Gaston Bachelard calls a reverie of will, in this case interpreted as “I will puzzle this out.” Zbigniew Herbert once said, “It is vanity to think that one can influence the course of history by writing poetry. It is not the barometer that changes the weather.” And yet the barometer is an essential tool for translating the pressure of the atmosphere to help us forecast what weather is headed our way. In The Gold Tooth in the Crooked Smile of God, Douglas Cole has provided readers with a precise collection of atmospheric readings for the weather systems of human relationships and struggles. The poems in the collection blow and rumble, rage and grow still. After finishing the collection I felt tousled and sunburnt and invigorated. There is much beauty to behold in Douglas Cole’s compulsively readable poetry collection The Gold Tooth in the Crooked Smile of God. As a whole, these poems leave the reader with the feeling of movement in depictions of gritty landscapes and the people whose dreams and failures inhabit them. These places are filled with memorable characters who the poet presents to the reader without judgment, and often with an open-eyed wonder. The reader winds up feeling like a witness and a friend. Douglas Cole is a poet that America needs right now. The country is having a loud argument with itself; so loud, you almost forget that the majority of Americans aren’t shouting at anyone, they’re just trying to get by. Cole writes poetry for this America - for the man who sits down in a reading room out of the rain who “knows someone’s coming / to try and kick him out, / so he lowers his head / and sets up for a siege”, people “watching the world die wishing it weren’t”, and the hanged man who consoles himself with the thought that “I’ll never regret again / I’ll never choose badly again / I’ll never wait in line again”. Comments are closed.

|

Popular Topics

All

We Support Indie Bookshops |