Unsolicited Press

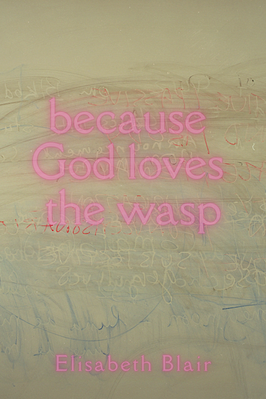

Elisabeth Blair is a Montréal-based poet and editor with an extensive background in music and visual art. She has been artist-in-residence at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts, Wildacres, and ACRE. Her publications include two chapbooks--We He She/It (Dancing Girl Press, 2016) and without saying (Ethel Press, 2020)—and poems in a variety of journals, including Harpur Palate, Feminist Studies, and Juked. Unsolicited Press has the privilege of publishing her first full-length collection, because God loves the wasp. Before you preorder a copy of her book, take a minute to get to know about her process and thoughts on writing. Favorite punctuation mark? Why? The em dash, for sure—it’s gorgeous, breathless, adaptive, helpful, noncommittal, suggestive… What inanimate object would you thank in your acknowledgements? The super comfy soft chairs at the University of Vermont library, which was near where I lived when I was working on much of this book. They are boxy and plush and you can curl up in them while swinging the attached little arm-desk around in front of you for a laptop or notebook. I wish I had one at home! Does writing energize or exhaust you? Each type of writing has different effects on me. I get super energized writing about poetry – like when I’m drafting my poetry craft newsletter, or offering a poet feedback on their poem or manuscript. Freewriting of any sort is deeply calming. Writing about trauma carries with it a special kind of deep focus, catharsis, and relief (though it brings with it a whole host of other emotions too). When writing fiction (whether in prose or verse form) I find it’s so challenging on so many levels that I get exhausted after only a few hours. It was only this year that I finally learned how to take cat naps, which help keep me going when I’m working on fiction-based projects. Have you ever gotten reader’s block? Yes! In the past I went through very long, 2-year-ish cycles, where I was either reading a lot or reading very little. I always thought about it as a consuming mindset vs. a producing mindset. Ideally you want to have both, but in practice, if I was in a production phase, I could only read a few pages of a book before I’d start wiggling in my seat like an impatient child and then leap away to write—I just had too many ideas. Whereas in the consumption phase, I was open, calmer, and had more room for new words, new ideas. Over the last 5 years I’ve been able to balance this cycle out through teaching. To prepare for giving a workshop, I need to read all sorts of wonderful stuff, so I’m always regularly reading—especially poetry. And I’m so glad — it’s such a great side effect of teaching. Do you think someone could be a writer if they don’t feel emotions strongly? I think anyone who wants to be a writer can be a writer. There’s room for every one of us weirdos. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power? At around age 10, I discovered quite by accident the absolutely ghastly murder-suicide poem “In the Round Tower at Jhansi” by Christina Rossetti. Until then I’d only read childrens’ poetry (simpering or humorous stuff) and never really took to it—but this poem gave me shivers to my bones! I’d often re-read it in secret, scaring myself silly. Then at age 13, I had to make a poetry anthology for class. To find poems, I wandered through the public library opening books at random, and happened upon “A Lovely Love” by Gwendolyn Brooks. At that time in my life I was experiencing the intensity of first love, and I was astonished at how this strange, musical writing deftly portrayed wild, passionate, secret (!) love. Both these experiences profoundly affected me. No movie I had ever seen—despite all the money and resources in Hollywood—had affected me like these tiny poems had. It was clear to me that poems wielded enormous power. How many unpublished and half-finished books do you have? I’m working on three main manuscripts right now—a giant erasure poem, a novel in verse, and a sci-fi novel. Then there are 3-4 other bits and bobs that might assemble themselves into a manuscript in the future, but which are currently just poking around on the sidelines. What does literary success look like to you? Literary success takes two forms. The first is supporting myself financially with my writing and writing-related activities. This is pretty easy to measure (if near-impossible to achieve). The other is more difficult to measure: I would like to earn the respect of those whom I respect—to become a valued peer in the eyes of my literary idols. What did you edit out of this book? The early drafts had a lot of teenager-y sarcasm, bite, and bitterness to them. I had to first let my 16-year-old self have her say—exactly the way she wanted to say it—before I could gently guide those snipes and rages into more sophisticated poetic expressions of these same emotions. If you didn’t write, what would you do for work? If I wasn’t creative, I think I’d love to be an entomologist. Bugs are the best!  A memoir in verse, Elisabeth Blair’s because God loves the wasp documents two and a half years she spent living in two abusive facilities for “troubled teens” during the late 1990s. The wilderness camp and emotional growth boarding school were modeled on the teachings and tenets of Synanon, a mid-20th-century cult. ORDER TODAY. Comments are closed.

|

Popular Topics

All

We Support Indie Bookshops |